The Language of Human Performance

A periodic-table approach to standardize decisions across the human performance model

In my previous posts, I discussed the definition of human performance and how it relates to both readiness and preparedness. I explained how readiness ties directly to monitoring stress and managing adaptation, and how preparedness ties to the specific trainable physical fitness qualities. That discussion covered the “what” of human performance, but it still leaves some confusion about the “how” of developing and managing a human performance model. The ability to tie everything together under the umbrella of human performance can make the difference between high levels of success and massive failure. Because this is such an important topic, we should take some time and talk about it.

Challenges in Athletic Development

When working with athletes, sports medicine and sports performance professionals face many challenges. These challenges create the gap between the two groups, making it harder to provide a seamless transition for those who are acutely injured and trying to return to play, and for those seeking to improve physical performance. At times, these issues become the rate-limiting factors between winning and losing. To eliminate them, we must first recognize them so we can make meaningful and lasting changes.

In sports medicine, several factors make efficient recovery difficult. These include managing injuries while balancing athlete health with sporting demands, addressing mental health, and navigating the ethical dilemma of returning athletes to play as quickly as possible while respecting tissue-healing timelines. One of the biggest challenges is the lack of a standardized process that brings everyone together and keeps the athlete at the center of care.

In sports performance, improving physical performance also presents obstacles. Key challenges include preventing injury while avoiding overtraining and optimizing recovery, and managing the time commitments of training alongside sporting demands. Modulating training intensity while ensuring adequate recovery is difficult when athletes are pulled in many directions. As in sports medicine, managing the psychology of the athlete is ongoing; many athletes struggle with performance anxiety and fear of failure, and need help maintaining focus and avoiding negative self-talk and fear-avoidant behaviors. A major barrier for performance staff is inconsistent or poorly coordinated systems that fail to keep everyone aligned on training loads and recovery strategies.

How to Eliminate the Gap

The consistent challenge for both sports medicine and sports performance is the absence of a standardized process and the presence of inconsistent, poorly coordinated systems. This lack of a shared model is the reason the gap exists. To eliminate it, we need a common language that speaks to both rehab and training, and a model that encompasses all aspects of human performance. It’s often suggested that movement is the language of human performance, but there are many things we do in a human performance model that do not involve movement.

So what is the common denominator that ties everything together? In my opinion, it goes back to biology. Everything we do in our model is geared toward the human organism. Since humans are governed by biological principles, our common language should be based on the most fundamental of these principles: the general adaptation syndrome. This is the process by which the human body responds to physiological stress. The organism encounters a burden from the external environment — what we call a stressor, or the term I prefer: load. The body’s reaction to external load creates an internal stress response that initiates the general adaptation syndrome. Because load is the catalyst for the stress response, it becomes the common language we can use to communicate between rehab and fitness.

The Language of Human Performance

With load as a common language that ties together both sports medicine and sports performance, we can build a systematic model that connects all aspects of human performance. A model is a structured approach that represents the relationships and interactions between components, not just the parts in isolation. An effective model must encompass our assessment process, the interventions we use during rehabilitation and training, the way we monitor and quantify load, and the recovery strategies we promote.

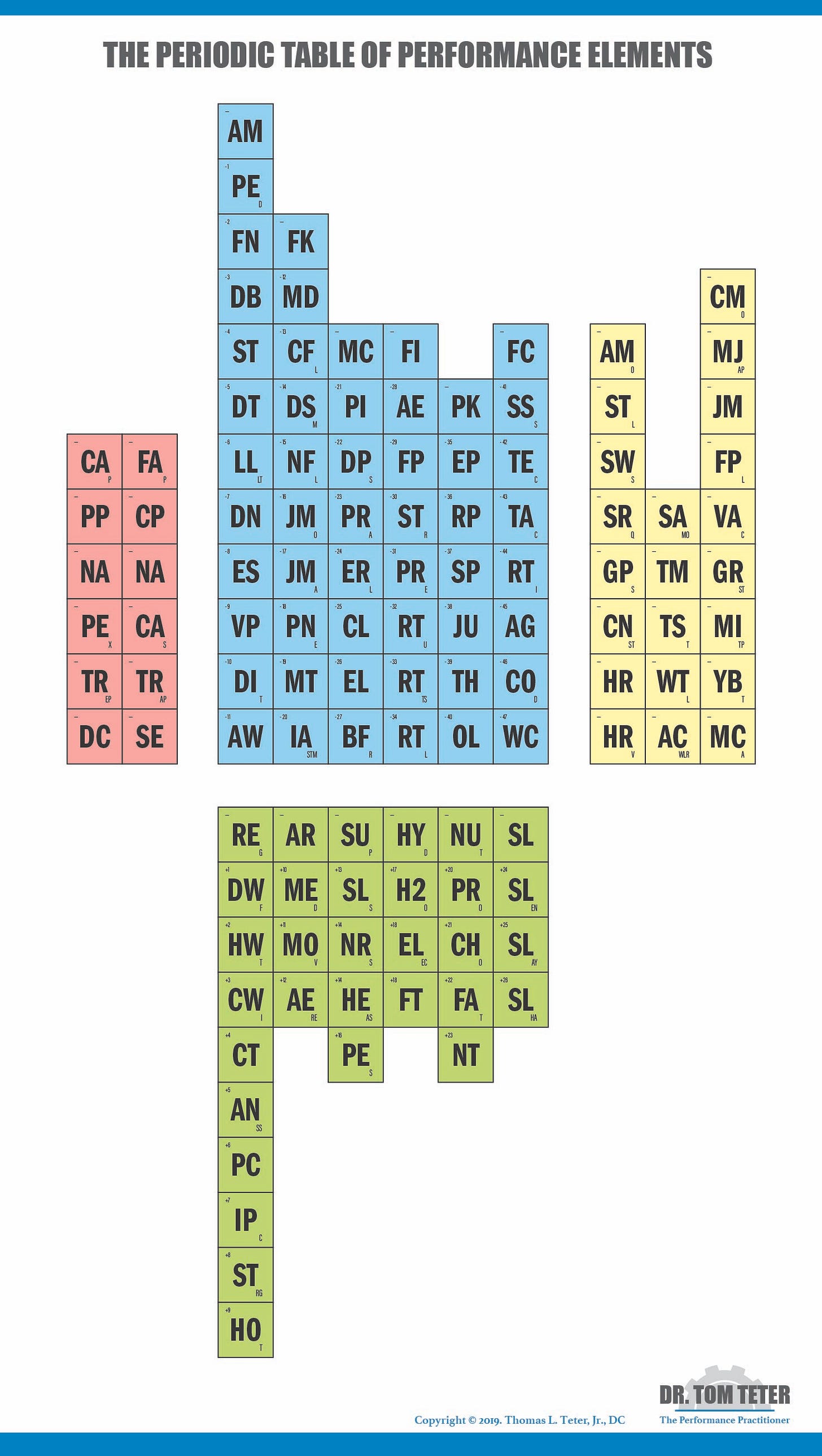

My model was influenced by the periodic table. In chemistry, the periodic table classifies elements into like categories and quantifies them by atomic weight. It is organized into four rectangular blocks that show similar characteristics and allow us to predict behaviors. Elements are arranged in columns of similar elements, with atomic weights increasing from left to right and top to bottom. Using the periodic table as a template helps us see trends and configurations that let us organize our model systematically and efficiently.

The Periodic Table of Performance Elements

My periodic table of performance elements mirrors the look and feel of the chemistry table. It has four groupings of elements with similar characteristics. Each element carries a theoretical load score based on its perceived stress response to the human organism. Organizing elements this way creates a roadmap for designing a human performance model and establishes standard operating procedures so everyone uses the same playbook. Using load as the common thread removes professional bias by forcing us to consider what we are doing, why we are doing it, and how each interaction affects the organism. It encourages a collaborative system for the integrated support team instead of silos without direct interaction.

Each grouping is color-coded:

Red: Audit elements.

These are the entry points into the system and provide standard operating procedures that prevent skipping steps and ensure reproducibility across practitioners. Audit elements make sure the athlete or patient starts in the right place for optimal results. They have a neutral effect on the organism. We use both clinical and fitness audit processes.

Blue: Intervention elements.

These represent how we do our work with patients or athletes. The intervention elements align left to right along the six stages of care in the rehabilitation continuum: acute management, foundational kinematics, motor control, functional integration, progressive kinetics, and fundamental capacity. Under each stage, elements align vertically to meet the therapeutic goal of that stage and are ordered by their theoretical load score from least to most stimulative. As with the chemistry table, lower-load elements appear at the top left, and higher-load elements at the bottom right. Intervention elements have a negative effect on physiology (they create stress that we must recover from).

Yellow: Monitoring elements.

These quantify the loads the athlete encounters and how those loads affect the stress response. Monitoring elements let us check our work during interventions. Monitoring is a core part of readiness. Our model uses acute, subacute, and chronic variables to monitor stress. Each category contains specific methods for quantifying load. Monitoring elements have a neutral effect.

Green: Recovery elements.

These are the specific tools we use to return the individual toward homeostasis — the second part of the readiness equation. They are organized into six categories that make up the recovery continuum: regeneration techniques, active recovery, supplements, hydration, nutrition, and sleep. The recovery elements are placed from least effective to most effective moving left to right. It stands to reason that passive regeneration has less effect than sleep on returning an athlete to homeostasis. Recovery elements have a positive effect on the organism.

Practical Application

Using the periodic table of performance elements gives us a comprehensive roadmap to guide clinical practice. It encompasses all aspects of the human performance model and creates a common language — load — that supports collaborative communication. The table brings everyone together, regardless of professional designation, and lets each person highlight their strengths within a model that doesn’t discriminate based on titles. Each provider on the integrated support team can choose elements they are confident delivering and form partnerships in areas where they have less experience or training. This approach breaks down silos by removing professional labels and focusing on individual strengths and comfort levels.

A common language lets every team member work from the same playbook and share a clear understanding of what we’re doing, why we’re doing it, and how it affects the athlete under our care. Using this model not only closes the gap between sports medicine and sports performance — it helps ensure the gap never appears. The periodic table of performance elements also reveals blind spots in a clinical system. I often ask providers to take a red marker and cross out every element they are 100% confident they can deliver or for which they have formal education. When they’re done, they can see where to direct further education or where to build strategic partnerships with providers who have those skills.

My model of human performance is not perfect and is constantly evolving, but it has given me a formalized structure to provide comprehensive care and to guide my search for answers to questions I didn’t yet know to ask. Consider your own model and how you can eliminate the common challenges between professions. In my experience, these challenges can be reduced by creating a common language that ties everything together. I have found nothing better than the application of load. Load is the catalyst for the long-term physiological adaptations we seek in both rehabilitation and fitness, so it makes sense to center load as the star of your performance model to achieve optimal results.

If you want a reproducible way to connect rehab and performance, the Certified Clinical Human Performance Practitioner (CCHPP) course walks through every element on the table — audits, interventions by stage of care, load monitoring, and recovery plans you can defend. See the syllabus here.